Discover in this land a long tradition of historical authors: rising in the centre of Magna Graecia, Reggio Calabria has been a fertile ground for writers and poets who have documented its history and told of its traditions imbibed with history, poetry and music.

Stesicoro

Stesichorus’ original name was Teisias, which means "chorus instructor". We are almost certain that he was born in the Calabrian Metauros (what is known today as Gioia Tauro). Stesicoro was a citadero: he recited his work, that is, by accompanying himself with a lyre. He was considered by the ancients as the Homer of choral poetry. His work is divided into as many as 26 books, of which only a few selections remain. He ventured into many diverse genres, from epic to pastoral, to erotic poetry. Stesicoro told the story of the Trojans according to its most famous version, namely the one that accused Helen of being an adulterous women, as well as the cause of the long and bloody Trojan war: the legends says that for this reason he was punished by the Dioscuri, blinded, and then regaining his vision after retracting it in his subsequent works.

Ibycus

Ibycus was the Greek poet of an aristocratic family who would have been trained at the school of the famous Sicilian poet, Stresicoro. He moved to Samo and lived at the court belonging to the tyrant Eace, of which his arrival on this island is dated at around 564-540 BC, or, at the court of Policrate’s son, for whom the likes of Eusebius fixes the arrival of the poet in Samos around 536-532 BC. According to tradition, this trip was motivated by his refusal to become the tyrant of Reggio. Only a few selections of his poetry still exist, less than 100 lines, which are devoted to topics of eroticism and love. According to legend, he fell to some thieves and his death was avenged by a flock of cranes that led to the discovery of his killers. He would have been buried in Reggio Calabria.

Nossis

Nossis lived in the early third century BC in the Greek colony of Locri. She was a well-known artist due to her total dedication to the female universe, to the point that she was nicknamed the “voice of women”. That which distinguished the talent of Nossis was her vast literary awareness, as can be clearly discerned in a poem where she mentions herself and elucidates the gist of her epigrams: “Nothing is sweeter than Love; and every other joy is second to it: even the honey I spit out of my mouth. So Nossis says. And one whom Aphrodite has not kissed does not know what kind of flowers are her roses” (Palat. Ant. V - 170). Precisely this attention to detail of womanly life makes the few verses of this poetess into small pearls of the ancient female quotidian: we do not know if these glimpses belonged to the existence of a noblewoman or a courtesan. Nonetheless, to this day, she should be numbered among the great artists that flourished in the Province of Reggio.

Baarlam

Barlaam of Seminara, also known as Barlaam of Calabria, was a mathematician, a philosopher, a Catholic bishop, a theologian and a scholar of Byzantine music. He also wrote about arithmetic, music and acoustics. He was one of the most ardent supporters of the reunification of the Churches of the East and West. Along with two students of his, Leontius Pilatus and Boccaccio, he is considered one of the fathers of Humanism. Barlaam was a teacher of Greek and Latin to Francesco Petrarch and Giovanni Boccaccio, who made a major contribution, through the rediscovery of ancient Greek texts, to everything that not long after would be developed by the humanist movement. The humanist Giannozzo Manetti was the first to mention Barlaam in his biography of Petrarch. Although part of Barlaam’s work was lost, we still have many of his writings: booklets on various topics, usually short, but full of thoughts. Most of them are still unpublished.

Leonzio Pilato

He was a born in Calabria and he was the first translator of Homer. He also translated Euripides and Aristotle. He liked to call himself “Thessalus, like the great Achilles” as he felt a strong sense of attraction and belonging to the Greek world and the land that he believed to be his spiritual and literary homeland. Leontius Pilate, through his pen, counteracted this catastrophe and kept alive the spiritual, philosophical, cultural and aesthetic values of Greece. He provided the West with the tools they needed to draw on Greek sources and thus lay solid foundations for Humanism. A pupil of Barlaam da Seminara, Leontius Pilate must also be remembered for having obtained the first university chair in litteras graecas in Italy, thanks to Boccaccio, who hosted him in Florence in 1360. He died, shipwrecked, during the crossover that took him from Constantinople to Venice.

Tommaso Campanella

With Bernardino Telesio and Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella was one of the main representatives of Italian Renaissance thought. He entered the Dominican Order as a teenager and devoted himself passionately to the study of philosophical and scientific disciplines. Influenced by Bernardino Telesio, Campanella was accused of practicing magic. Tried in an ecclesiastical court, he was served an injunction to abandon his anti-Aristotelian doctrines. Driven by millenarist ideals, he plotted to establish a theocratic Republic conceived as the beginning of a general renewal of the world. The discovery of the conspiracy (1599) cost him a prison sentence for attempted rebellion and heresy. He avoided the death penalty by simulating madness (as a response to any question posed, he repeated obsessively: ";ten white horses"), and for 27 years he was imprisoned in the Castle of Naples. During this period of forced inaction, he composed many of his major works. Eventually released from prison, but still opposed by many in Rome, he led a difficult life for some time until he was forced to take refuge in France, where he was welcomed. Among his most important philosophical and literary works we should mention De sensu rerum et magia, La Città del Sole and l’Apologia di Galileo.

Nicola Giunta

Nicola Giunta is perhaps the most famous Reggio poet of all time, aside from also being a comedy and dramatic writer, and lyric actor. He trained under the influence of Carducci and D’Annunzio. His production is divided into satirical, lyrical, and fairy tales, which made the most famous poet of the Calabrian dialect. Poems such as Diu, Chistu è lu mundu, Paci, Malincunia d’Ottobri and Cori link to the Italian dialectic genre of his time, moving away from the parochialism. Among his people, he will conceive of his masterpieces, exalting the certain peculiarities of his people. He was a connoisseur and scholar not only of the regional dialect, as well as following the developments of the vernacular on a national level. Few other poets have known how to capture the spirit of the Reggio people like he has. His poems “‘A Funtana ‘i Rìggiu” and “‘U paisi ‘i Jufà” are declarations of love as well as regret towards his people and homeland.

Corrado Alvaro

He was born on 15 April 1895 in San Luca, a small town in the province of Reggio Calabria. He began with a small book dedicated to Polsi in art, legend, and history. In 1915, called to battle, he was wounded in the arms on the Karst, and was decorated with a silver medal. In 1917, the “Green Poems” were published in Rome. He moved to Milan with his family, where he was employed by the “Corriere della Sera,” the Italian national newspaper. During 1930, he published three short story collections (“Gente in Aspromonte,” “Misteri e avventure,” “La signora dell’isola”) and the novel “Vent’anni.” He began working for the cinema and a screenwriter and scriptwriter, and has film reviews in the “Nuova Antologia.” From 25 July to 8 September 1943, he took over the “Popolo di Roma”: with the German occupation of the city, he was subject to an arrest warrant and took refuge in Chieti, under the false name of Guido Giorgi, and survived giving English lessons. In January 1945 he founded, together with Francesco Jovine and Libero Bigiaretti, the National Union of Writers. On 20 April 1956, his last article was published in the “Corriere della Serra”, where he had returned to work. He died in Rome on 11 June.

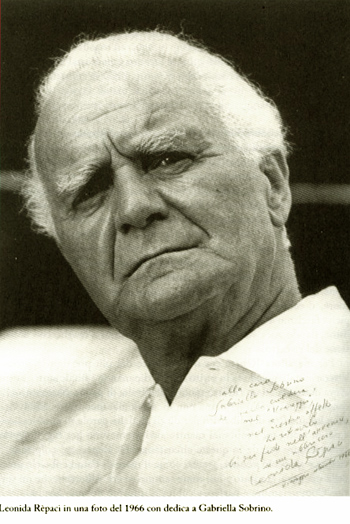

Leonida Repaci

Leonida Repaci spent a humble childhood in his city until the catastrophic earthquake of 28 December 1908 that devastated Messina, Reggio, and the surrounding areas. His family’s home was also destroyed. Leonidas was then sent to Turin, where his brother Francesco practiced law. When the first world war broke out, he departed for the front, becoming an Alpine officer. For the courage and bravery shown on Monte Grappa, Repaci won a silver medal for military valour. He subsequently joined the Socialist Party in Turin, participating in the “Workers’ Movement” and collaborating on the “Ordine Nuovo” with Gramsci. In 1924, he collaborated on the first issue of “L’Unita” and for the same newspaper he translated “Il tallone di ferro” of London. He died in Pietrasanta (Lucca) on 19 July 1985. Repaci's work goes hand in hand with his direct life experience of life. The Storia dei Rupe was autobiographical and consisted of an entire cycle – I fratelli Rupe (1932), Potenza dei fratelli Rupe (1934) and Passione dei fratelli Rupe (1937) – which was subsequently published by Mondadori as a three-book omnibus. It was followed in 1969 by Principio di secolo and Tra guerra e rivoluzione, and then, in 1971, by Sotto la dittatura, and, in 1973, by La terra può finire.

Lorenzo Calogero

Lorenzo Calogero was born in the small town of Melicuccà, in the province of Reggio Calabria. He had success while studying medicine, but at the same time, he read the works of various poets and began to write: during this period, he composed a good part of the verses that formed the “25 Poesie”, “Poco suono” and “Parole del Tempo” collections. Having received a Catholic education, he followed the literary scene that gathered around “Il Frontespizio”, by Pietro Bargellini and Carlo Betocchi, to whom he sent his first poems in the hope that they would be published. In 1936, his first book, Poco suono, was published at his expense by Centauro Editore. In 1937, after getting his degree in Medicine, he continued his correspondence with Betocchi, who promised to publish his works in “Il Frontespizio”; it did not happen, and he drew the conclusion that he was not destined to be a poet. He began distancing himself from writing, and for several years we find no trace of any attempt to publish or to be in contact with the literary world. He spent his last years as a solitary poet in his native country, dedicated to poetry. He died in Melicuccà on 25 March 1961.

Mimmo Gangemi

Gangemi is a civil and clinical engineer. He has published several novels, some of which have won literary prizes: “Un anno d’Aspromonte” (Rubbettino, 1995), a debut novel in which that featured a rewrite in 2014, “Il Prezzo della carne” (Rubbettino);” Quell’acre odore di aglio” (REM, 1998), rewritten and published by Bompiani in 2015 with the title “Un acre odore di aglio”; “Pietre nel levante” (So.Se.d, 2001); “Il passo del cordaio” (Il Sole 24 Ore, 2002); “25 nero”(Pellegrini Editore, 2004); the trilogy “Il giudice meschino”(Einaudi, 2009, winner of the Bancarella Prize in 2010),” Il patto del giudice” (Garzanti, 2013) and ”La verità del giudice meschino” (Garzanti, 2015); “La signora di Ellis Island” (Einaudi, 2011). He collaborates with various magazines, and since January 2010, he worked as a commentator/editorialist for “La Stampa.” He writes the “Calabria on Web” column and manages the website of the Regional Council. He is a member of the Tropea Literary Prize and Giuseppe Berto Prize juries. He has worked as a screenwriter for television as a playwright for the theatre.

Gioacchino Criaco

He made his debut in 2008 with the novel “Anime nere”, from the film of the same name was directed by Francesco Munzi. The film was the winner of nine David di Donatello, three Silver Ribbons, and the Sergio Amidei award. He then published the novels “Zefira”(2009), “American Taste”(2011) and, for Feltrinelli, “Il saltozoppo”(2015) and “La maligredi” (2018). His novels have been translated worldwide in numerous languages.