The story San Luca began a long time ago in Magna Graecia, but the earliest and most definite traces of human settlements take us to the end of the year 1000, when the Saracens plundered the ancient village of Pietracucca, in all likelihood situated at the foot of the stone monolith of Pietra Cappa. This traumatic event prompted the subsequent transfer of the community to the area of Pietra Castello. Here, at the foot of the majestic rock formation, a new village was established with the name of Potamìa. Over the following centuries, the village was able to take advantage of the protection provided by the Byzantine fortifications. Then, with the advent of the Normans, it was incorporated in the feudal estate of Sinopoli, which included lands on both the Tyrrhenian and the Ionian sides. With the Swabians, the area come under the control of baron Carnelevario de Pavia, and, later on, that of Fulcone Ruffo, Antonio Centelles and Tommaso Marullo. In the late 16th century, Potamìa, together with other territories, fell under the rule of the Marquis of Bovalino, Sigismondo Loffredo, but shorty afterwards a violent flood destroyed the village and the inhabitants were forced to a new exodus. On 18 October 1592, the survivors, headed by the bishop of Gerace, identified a new site, which was renamed San Luca as a tribute to Saint Luke the evangelist. After being governed by a succession of feudal lords, in 1811, San Luca became an independent municipality. During the course of the 20th century, the small town was confronted with a series of catastrophic natural disasters, from violent earthquakes (with special regard to the one of 1783) to the floods of the 1950s and 1070s, which disrupted the physical aspect of the town, and especially its most ancient district dating back to the 17th century, as well as its social and economic fabric.

What to see

Significant traces of the past can be discerned in what is left of the medieval castle, the monasteries of Saint Stephen, Saint Constantine, Saint George and Saint John, and the Norman Abbey of Saint Nicholas of Butramo. Indubitably, though, the key attraction of the area, the pulsating heart of the religious spirit of the entire province, is the Sanctuary of Polsi. A place of Marian worship and a pilgrimage site visited by thousands of faithful coming primarily from Calabria and Sicily. Another important place of worship is the Church of Saint Maria of Pity that houses a painting of the Deposition from the 17th century, some statues coming from Potamìa, including statues of Saint Luke, Our Lady of Sorrows, Saint Francis Xavier, and the highly valuable statues of Saint John and the Risen Christ. Testimonies of the Byzantine heritage are the remnants of the 10th century church of Saint George, rising in the district by the same name, in the past, a meeting place for worshippers and hermits. The area of San Luca has much to offer also in terms of uncontaminated natural landscapes. An example is the area of the lago Costantino, a body of water formed in the wake of the flood of 1973 and the subsequent landslide that created a veritable natural dam obstructing the course of the Bonamico torrent. Initially called Oleanders Lake, the body of water then took the name of a nearby 10th century monastery, of which today only remnants are left. After reaching a perimeter of about 5 km and a depth of 18 metres, over the years, the lake gradually disappeared due to the sediments carried by the torrent, which progressively reduced its width and depth. The entire area has been rediscovered for its naturalistic and landscape features by several environmentalist and excursionist associations that have created suggestive trekking paths.

The Valley of the Big Stones

One of the emblems of the Aspromonte National Park, whose beauty is breath taking, Pietra Cappa is one of the tallest monoliths in Europe. It combines the fascination of an uncontaminated landscape with the mystery associated with the legends that surround this territory and the entire Valley of the Big Stones. One of the most popular legends handed down from the past says that Jesus, after asking his disciples to collect stones for penance, picked up a small stone left behind by Saint Peter and converted it into the gigantic rock formation. Always in the area, between the towns of San Luca and Natile, we find other fascinating and imposing monoliths, such as Pietra Longa, Pietra Stranghiò, Rocce di Febo and Pietra Castello. In particular, the latter, made up of a number of boulders, owes its name to its position typical of a fortress as well as to the remnants of a castle from the Byzantine period. Among the many legendary tales about the castle, we should mention the one of Atì, young countess from Potamìa, whose spirit, the legend has it, is still trapped in the valley, so that inhabitants and shepherds from the area claimed they had seen her in the distance, especially on nights of full moon, intent on gazing at the horizon and placating her tormented soul. Of particular interest are the Rocks of Saint Peter, rock formations used as shelters in ancient times (clearly visible are the cavities excavated in the rock) by Greek rite religious men and hermits and Basilian monks around the year 1000. Another favourite destination with excursionists is Montalto, the highest peak in the Aspromonte massif. A meeting point for hiking – and especially canyoning – experts and enthusiasts is the bed of the Butramo torrent, which cuts across the Infernal Valley amidst immense gorges and spectacular slopes, preserving an extraordinary natural heritage typical of the Aspromonte region.

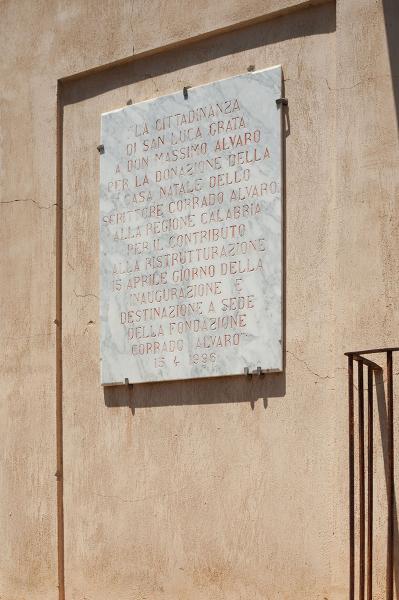

The native house of Corrado Alvaro

A distinguished son of San Luca is Corrado Alvaro, one of the most important authors from Calabria and one of Italy’s most celebrated 20th century writers. Open to the public is the writer’s native house situated near the Mother Church, in a three-story building from the 19th century. The house retains the furniture of the time, the bedroom and the books of the author of “The People of Aspromonte”. The building also houses the Fondazione Corrado Alvaro: established to promote the memory and the cultural heritage of the illustrious writer, journalist and poet, over time the foundation has become widely known as a place for the study, research and promotion of the works by Alvaro and southern literature in general.