Situated at an altitude of 527 m above sea level, on a rock in the heart of the Amendolea torrent region, with the mighty Mount Cavallo towering behind it, stands the ancient Griko speaking town of Roghudi, whose name comes the Greek word "rogòdes", meaning full of crevices, or "rhekhodes", harsh. The early origins of this small village take us back to 1050, when it was a small portion of a larger Griko speaking area. Between the 11th and the 12th centuries, it was under the control of the Bovas. Some time later, it came under the influence of the Stato dell'Amendolea, which continued until 1806. Also because of its rather impervious location, over the centuries Roghudi has suffered greatly from natural disasters. In 1971 and 1973, two violent floods resulted in the death and disappearance of many people and damaged many homes, forcing the population of about 1600 people (most of them moved to present-day Roghudi, built from scratch on the seacoast) to abandon the village, which thus began its new and fascinating existence as a ghost town.

Mysteries and legends

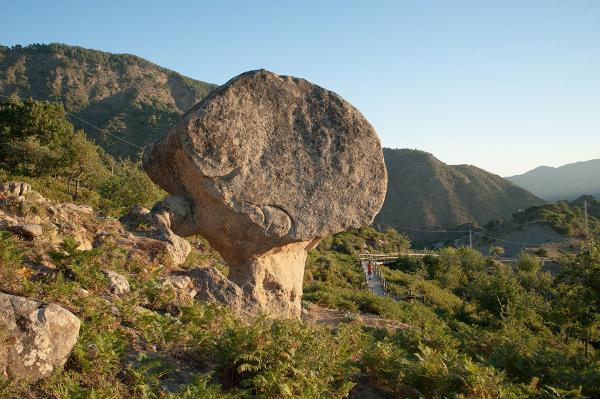

Today, the original town, Roghudi Vecchio, attracts the most attentive and discerning visitors, especially those who love places shrouded in mystery and uncontaminated natural landscapes. This is the tapestry woven by history, man and nature in Roghudi Vecchio, which nowadays is represented by the remains of dwellings perched on the edge of precipices, narrow lanes, fascinating glimpses, and a small trace of devoutness enclosed in the small, recently restored, church of St. Nicola. A place that is frozen in time, but whose deepest souls still seem to speak to the visitor. According to a well-known legend, one of them intones at night the incessant lament of the children who lived here: the children met with a sad fate, falling into the many crevices that characterised the old village. It is no coincidence, in fact, that it was an established practice in Roghudi to drive huge nails into the walls of their homes, to which the women secured their children by the ankle, precisely with the aim to prevent such tragedies form occurring ever again. Other significant legends are associated with the nearby village of Ghorio di Roghudi, now abandoned. This is where it is possible to observe special rock formations called "Rocca tu Dracu" (Rock of the Dragon) and "Cauldrons of Milk". According to popular tradition, the latter were the source of nourishment of the dragon, who, in its turn, was believed to be the fearsome guardian of an inestimable treasure.

The “Narade”

Of a “passionate” nature, instead, is the legend that envelopes contrada Ghalipò, a place populated by women (referred to as “Narade” or “Anarade”) having feet in the shape of mule hooves. Unsettling creatures, whose purpose was to have sex with the men, they posed a thread to the women, who were taken by deception to the river and killed. To ward off this danger, three gates were built on as many different accesses to the village. According to some sources, this legend could be linked with the myth of the Nereids, immortal creatures who were attendants to Poseidon, the god of the sea, or with that of the Naiads, the nymphs of fresh water. However, aside from possible assonances between Greek mythology and the culture of the Griko-speaking region, it should be noted that the latter is rich with references to universes populated by monstrous creatures and spiritual beings.

Griko

A living testimony of the cultural influences and linguistic contaminations still present in this territory, with the complicity of the Hellenistic-Byzantine imprint, and a more direct connection with the Greek spoken in Magna Graecia, is Griko, the language spoken by the Griko people of the region. This special dialect was used throughout southern Calabria until the 16th century, and even contains some words from the Archaic (Doric) period, which are totally unknown to Modern Greek. Nowadays, this language continues to be spoken by small groups of inhabitants and an effort it being made to underscore its value and cultivate it through initiatives promoted by associations and the local Greek linguistic community.

Uses of the broom

In the old days, in Roghudi, an ancient art was passed on from mother to daughter: it was broom processing. A practice that, today, is preserved by few people, but in the past was used widely to make fabrics and clothes. The stems of the plant, generally harvested in the month of August, were macerated, rendered pliable and made into skeins. Then it was up to the loom and the skills of the weavers to transform the rough cloth into useful garments or fabrics.